The Story of a Freeski Mountaineering Adventure in Mongolia

This article has originally been published in Backline Magazine in December 2013. The text below has been slightly adapted and features different images.

Uka looked worried. Uka was normally the relaxed “You don’t worry my friend” kind of guy and our cook. He exchanged concerned looks with our Mongolian translator Tsogo. The kitchen tent of the base camp was caving in with strong gusts and on the brink of breaking down. The girls tent had already fallen victim to the snowstorm. Everyone was running around securing the remaining tents with extra ropes and rocks we dug out of the freshly fallen snow.

We were halfway through our two-week mission in the remote Tavan Bogd mountain range in Mongolia. It was winter in the middle of May and it felt like we were completely out of touch with the rest of the world. Everything was colder, windier and icier than we expected, but when the weather was clear it was also more impressive and overwhelming under the biggest sky you can imagine.

Our goal was to explore these mountains for interesting skiable lines and bag a few of the 4,000 meter peaks along the way. Melissa Presslaber, arguably one of the strongest big mountain skiers in Austria, came up with the Mongolian idea the previous summer. She put together a team of like-minded ski mountaineers for this trip. Liz Kristoferitsch holds the Austrian Snowboard Freeride Masters title, Michi Mayrhofer competes in freeride contests, Zlu Haller is a well-known Austrian climber and photographer, Tom Andrillon is an accomplished French filmmaker and I, Stephan Skrobar, run a Freeride Center in Austria.

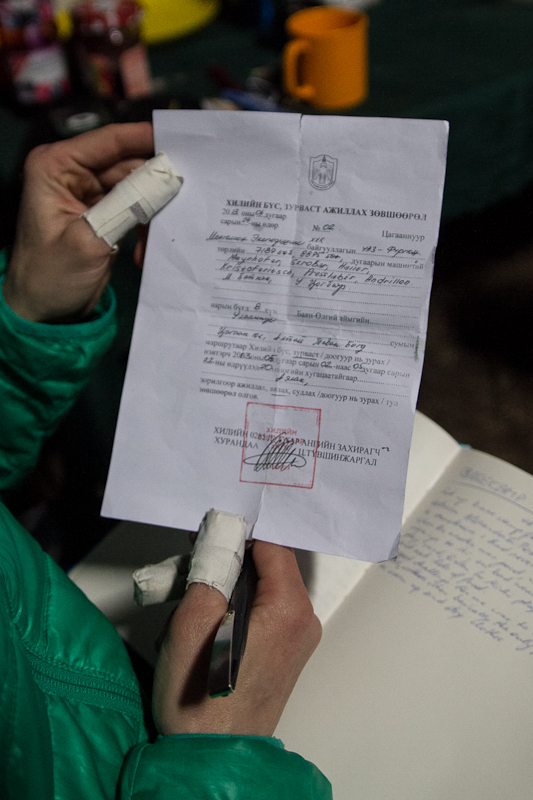

Organizing the trip was obviously a drag, but part of the experience. Getting immunization shots (expensive), obtaining visa and border permits (complicated), brushing up on rescue technique (necessary), wooing sponsors for gear (part of the game) and finally trying to fit everything into bags that won’t exceed airline limitations and won’t freak out airport staff. We failed miserably at the last point, and would like to apologize to the guy behind the desk at Munich airport whose day we definitely ruined.

Once in Ulan Bator, capital of Mongolia, we hooked up with Mongolia Expeditions who handled the logistics of our trip to the Altai. A local partner who organized food and transport and who would, eventually, bring us a lot closer to the Mongolian culture and way of life was an absolute necessity.

Olgii is a smallish city in the Bayan Olgii Aimag in Western Mongolia where we ended up spending a few days prior and after our time in the mountains. Olgii has a mentionable relaxed, friendly vibe. It is a place where cows battle it out with the few traffic lights and the sun settles in an incredible warm magenta. From there on we headed further west, leaving civilization.

It was a one-day trip through the steppe in one of those indestructible Russian vans, designed to go on roads where there are no roads. The end of the “road” marked the end of the day, so we camped and individually contemplated what lied ahead and what animals roamed these parts of the world beyond the tent flaps. Wild horses, sheep, yak, wolves, bears, wolverines. Camels took our gear up to base camp as we started the six hour hike, regularly stopping wide-eyed and drooling while scoping the mountains. Bigger, icier, wider, colder, windier than anticipated.

Preparing for the mountains of the Tavan Bogd range was difficult. The only map we had was a Russian scribble, “published” in 1969. Literature was rare, as far as we knew the first time a ski touched these areas was only ten years ago. We relied on our eyes, judgment, the daily weather report from Innsbruck via satellite. Snow conditions were different than expected, the exposure and hard winds coming in from China affected the snowpack immensely. The skiing, quite bluntly, sucked.

We set up camp at just under 3100 meters altitude, behind the moraine of the massive Potanin glacier. Life at base camp meant getting used to constantly living in various layers of down jackets, eating lots of horse meat and discussing how to deal with the thick sheets of ice that covered pretty much every mountain face we looked at. At least that last problem was going to be partly solved by the snowstorms that hit us later on.

We started exploring the area by climbing the mountain furthest away from base camp, Nairamdal. This peak is an easy but long hike to the end of Potanin glacier and marks the border between Mongolia, China and Russia. That’s about the only interesting thing to say about it, apart from the fact that the view is nice from up there. Russia to your right, China to your left, that is cool.

Then we got down to the serious business of freeski mountaineering. Not so much focusing on the actual summits, but the interesting lines that could be found on their faces. We started with obvious but intriguing colouirs on Burgit, the mountain across from our base camp, then ventured on to Naran, a beautiful mountain that sits between the Potanin and Alexander glacier. We climbed those colouirs partly alone, partly in small teams. Each of those climbs and descents added to the sensation of being very far away from civilization and possible help, but also intensified our concentration and the overall experience.

After five days in the camp snowstorms hit the mountain range. We spent two days in crisis management, debating weather reports, moving our base camp to a Ger – a sturdy Mongolian tent, playing cards and hiding in the sleeping bag.

When the skies finally cleared it got even colder, the snowpack was deeper and wind affected. We stoically skied big faces that looked good on camera but turned out to be fairly difficult to ski. And finally, on our last day, we left camp early to hike up Khuiten and ski its impressive North East face. Khuiten is Mongolia’s highest peak, and the weather report promised a sunny, albeit cold and windy day. Turned out the weather report was only partly right. When we reached the summit ridge after a seven-hour hike, another snowstorm hit us from China. We did the thing everyone will later tell you was “smart and responsible” and turned around just below the summit, but naturally it was a bit frustrating at the moment.

We returned to base camp and then back to Olgii a few days later, with a mixed feeling of achievement and failure. Of course it was neither. In reality it was an unbelievable trip to a great country.

Text: Stephan Skrobar

Pics: Zlu Haller / www.chalkjunkie.at

Further reading:

A skiadventure to Mongolia… (Melissa Presslaber)

Freeskiing Mongolia (Liz Kristoferitsch)

Camels and Skiing in Mongolia (Powder Magazine)

camelsarenevercold.tumblr.com (Behind the scenes pics, film trailer etc.)